If you have never flown into Orlando, Florida, you are missing a special treat. Inbound flights always include families with excited children on their way to visit Mickey Mouse and Cinderella’s castle. The children are anticipating miracles.

In April of 2015, my flight to Orlando seemed to be mostly filled by adult passengers, and I was disappointed. I got a nice surprise when we landed, however. As we were taxiing to our gate, and devices were turned back on, we heard an exuberant child from a seat somewhere in front of me:

“Oh, my good God! What are the odds?!! The Canucks go to the Stanley Cup play-offs, and we go to Disney World in the same year!”

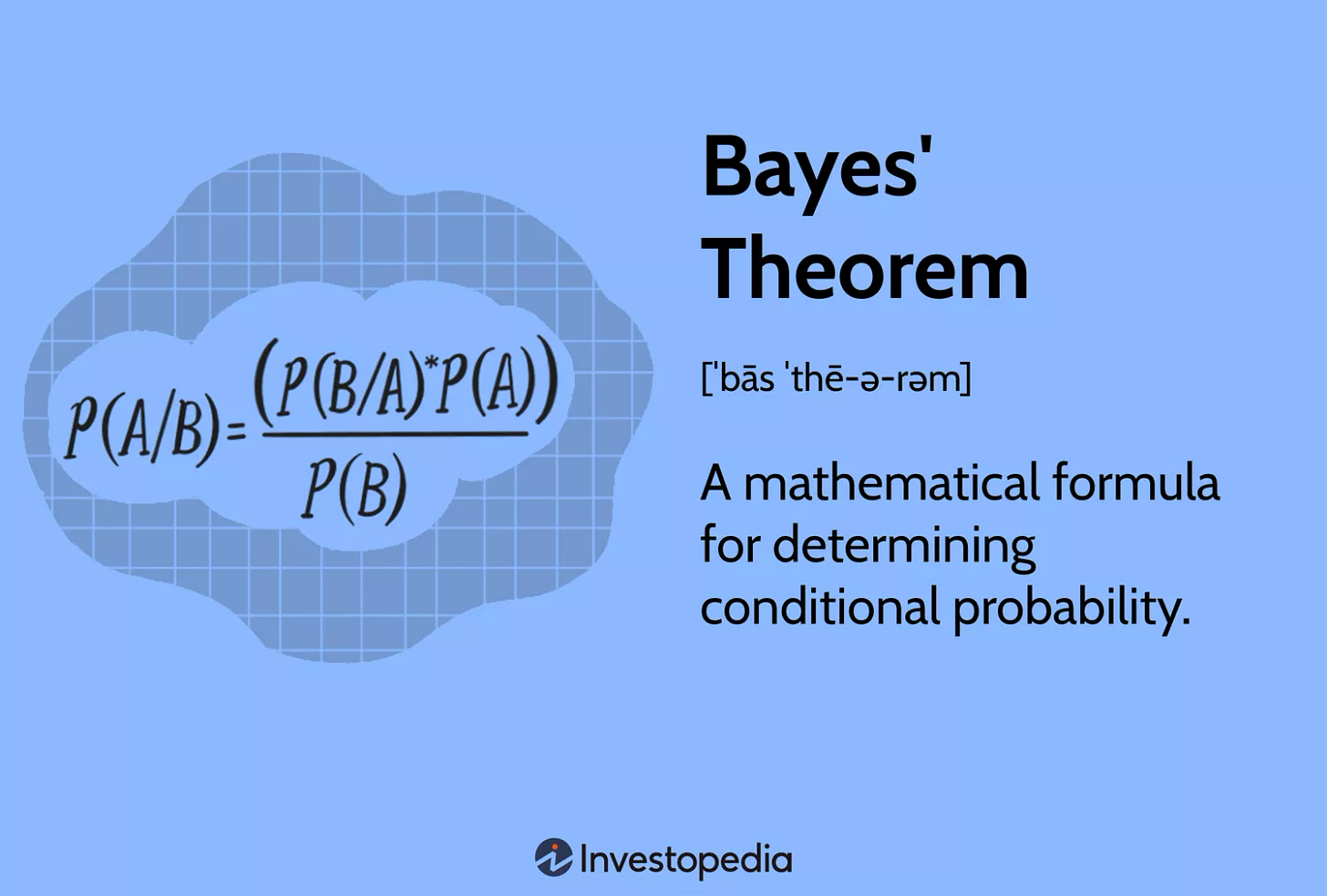

What are the odds, indeed? And how surprising is this child’s curiosity about the probability of co-occurring events? Allison Gopnik is a developmental psychologists whose research on children’s thinking has led her to propose that children appear to be students of the eighteenth-century mathematician, Thomas Bayes. Reverend Bayes’ treatise about probability was presented shortly after his death in 1763 to the Royal Society of London and was published in their Philosophical Transactions. His thinking grounds a branch of inferential statistics and has suggested an approach to epistemology that helps us understand the scientific method. Gopnik shows how infants deploy Bayes’ ideas in her books, The Scientist in the Crib, http://alisongopnik.com/TheScientistInTheCrib.htm and The Philosophical Baby, http://alisongopnik.com/ThePhilosophicalBaby.htm.

Generations of mathematicians worked on problems of inverse probability and the ‘doctrine of chances’ before Bayes proposed a sequential method of revising expectations for the probability of an event based on observed conditional probabilities. When I was introduced to Bayesian statistics in graduate school, I was delighted at how intuitively right it felt to think about inference this way. It did not occur to me until I read Gopnik’s research that Bayes felt intuitively right because this is the way we have been doing inductive reasoning since we were babies!

Reverend Bayes may have been motivated to think about probability after reading Hume’s argument against belief in miracles. Like Reverend Bayes, the little boy on my flight to Orlando, upon learning that his favorite hockey team had made it to the play-offs was confronted with something that seemed miraculous. Like Bayes, he was curious about how probable such a wondrous confluence of events might be. Truly, the questions that occupy philosophers arise in the questions of little children.

I remember this story! Love this, Marsha.